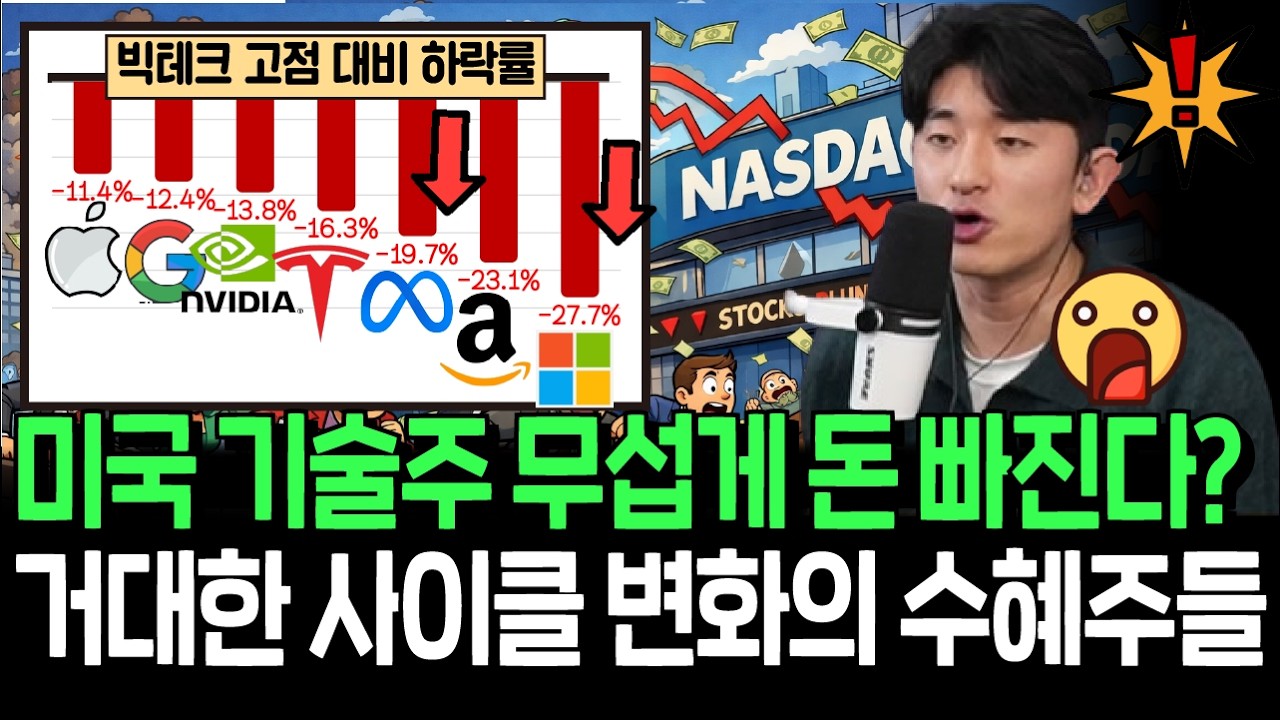

● Big Tech Bloodbath, Cash Exodus to AI Chips, Commodities, and Weak-Dollar Winners

Capital Rotation Out of Big Tech and the Nasdaq: Key Drivers Behind the Market’s Shift to New Leaders (Semiconductors, Commodities, and a Weaker Dollar)

This report consolidates six market developments in a news-style format.

1) Why capital is exiting Big Tech/Nasdaq for structural reasons rather than a routine pullback.

2) How “AI disruption” concerns propagated into financials (exaggerated elements vs. genuine risks).

3) Why Palantir, Robinhood, and AppLovin (recent momentum leaders) declined in tandem: the “leadership cycle” framework.

4) Why “AI infrastructure, memory, and data centers” remain resilient: where capital is reallocating.

5) Why the U.S. is lagging while Korea, Taiwan, Japan, Brazil, and Australia are stronger (USD weakness plus the industrial cycle).

6) An under-discussed factor: “private-market black hole” effects driven by IPO expectations for OpenAI and Anthropic.

1) Market Summary: “Capital is rotating out of U.S. growth equities into semiconductors, commodities, and non-U.S. markets.”

U.S. equities, particularly the Nasdaq and Big Tech, have declined by more than 10% from recent highs, weighing on broader sentiment.

In contrast, Korea and Taiwan (semiconductors), Japan (policy-related expectations), and Brazil and Australia (commodities) have remained comparatively strong.

This is better interpreted as a leadership transition and capital reallocation rather than a broad-based deterioration in the U.S. market.

Five variables are currently acting as primary drivers of flows:

interest rates, inflation, U.S. dollar weakness, semiconductors, and commodities.

2) Why Big Tech Is Weaker: Not Earnings, but an Investment-Cycle “Arms Race”

Positive headlines have had limited impact on prices, while modest negative developments have triggered outsized reactions.

Examples include delays in AI-related product communication being framed negatively for Apple, and Alphabet’s long-dated debt issuance being interpreted as signaling higher spending needs rather than balance-sheet strength.

2-1) Interpreting the Core Message

Big Tech is shifting from a “cash-rich” posture toward an “investment-expansion” posture, potentially reducing the relative appeal of shareholder returns (buybacks/dividends).

This reflects an unfavorable market setup for valuation rather than a deterioration in business fundamentals.

2-2) Key Tactical Constraint

Following earnings season, markets often require time to reassess forward cash-flow and margin implications.

Sentiment may shift if upcoming quarters either (a) demonstrate that higher capex preserves revenue and margins, or (b) provide signals of spending moderation.

3) Why AI-Disruption Concerns Hit Financials: The “Disintermediation” Narrative

A notable development is the sell-off extending into financials, traditionally less directly linked to AI cycles.

The narrative chain is as follows:

“Financial information (research/data) → AI summarization → pressure on information providers”

“Wealth management/brokerage → AI portfolio construction → pressure on intermediaries”

“Corporate stress → credit losses → pressure on banks”

This creates a cascading risk premium across the sector.

3-1) Assessing “Systemic Risk” vs. Overreaction

A meaningful portion may be exaggerated.

Management commentary (e.g., comparisons to prior robo-advisor concerns) supports the view that markets may be over-discounting disruption risk.

The pattern is consistent with aggressive pre-pricing of both positive and negative narratives, followed by partial reversal as realized impacts prove more incremental.

4) Why Palantir, Robinhood, and AppLovin Sold Off Together: Leadership “Digestion”

These stocks were among the key U.S. momentum leaders in 2024–2025, with cumulative gains on the order of 10x–20x over roughly two years.

When expectations have been heavily pulled forward, a loss of momentum often results in both price correction and time correction.

4-1) On Large Drawdowns in Former Leaders

A 50% decline is significant but not unusual among prior leadership stocks.

Historical patterns suggest leaders can enter prolonged consolidation phases after steep runs, with recovery requiring extended fundamental validation and renewed catalysts.

4-2) Where Leadership Has Shifted

Former leaders (Big Tech/growth software/select themes) → consolidating

Current leaders (memory semiconductors/AI infrastructure/commodities) → advancing

5) What Remains Strong: “Big Tech Capex Beneficiaries”

The market is differentiating between Big Tech as an equity factor and the industries receiving Big Tech investment.

As Big Tech increases spending, its own free-cash-flow optics and shareholder-return narratives weaken, while suppliers and infrastructure beneficiaries see more direct translation into orders, revenue, and guidance.

5-1) Key Flow Areas

Data center cooling and power infrastructure: strength supported by order growth (e.g., Vertiv).

Semiconductor value chain: constructive tone across TSMC, memory, and equipment (e.g., Applied Materials).

HBM and next-generation memory: ecosystem validation and supply-chain qualification news acting as catalysts within the Nvidia-linked landscape.

6) Why Non-U.S. Markets and Commodity Producers Are Stronger: USD Weakness plus the Industrial Cycle

Market focus has increased on commentary interpreted as tolerance for a weaker U.S. dollar.

Sustained USD weakness typically supports cross-border allocation into non-U.S. assets and can amplify performance in markets levered to industrial and commodity cycles.

6-1) Country-Level Drivers

Korea/Taiwan: semiconductor export momentum, particularly memory and AI-linked supply chains.

Japan: fiscal/policy expectations and related exposure to defense, trading houses, and commodity-linked value chains.

Brazil/Australia/Latin America: commodity-cycle sensitivity, often amplified under USD weakness.

7) Key Under-Discussed Variable: The “Private-Market Black Hole” from OpenAI/Anthropic IPO Expectations

Earnings alone does not fully explain the magnitude and synchronization of outflows from listed growth equities in certain windows.

A plausible complementary mechanism is liquidity preparation for large private-market AI deals, including pre-IPO participation and late-stage rounds tied to OpenAI and Anthropic.

Institutional investors may monetize portions of appreciated listed holdings to raise cash, with proceeds absorbed by private-market exposure and adjacent instruments.

7-1) “Related Assets” and Indirect Exposure

When direct access is constrained, demand can shift toward proxy exposures tied to early investors or strategic partners.

Price action can become more correlation-driven by perceived linkage rather than near-term fundamentals.

8) Near-Term Watchlist and Risks: Options Expiration, Seasonal Volatility, and Event-Driven Pullbacks

Between earnings seasons, thinner catalysts can increase volatility.

Options expiration events can further amplify short-term moves.

Late winter to early spring is often associated with heightened sensitivity to negative headlines, warranting reassessment of risk controls (cash, diversification, hedges).

9) Portfolio Implications: U.S.-Concentrated Exposure vs. Global Diversification

This environment is increasingly selective, characterized by narrow leadership rather than broad participation.

Three practical positioning frameworks are common:

1) Long-term accumulation: systematic exposure to high-quality growth/Big Tech with time diversification.

2) Seeking near-term relative outperformance: overweight semiconductors (memory, equipment, power, cooling) and commodities/energy aligned with current flow leadership.

3) Global diversification: increased regional diversification across Korea/Taiwan/Japan and commodity-linked markets, reflecting potential USD-weakness tailwinds.

10) Consolidated Conclusion

Big Tech/Nasdaq weakness appears driven less by earnings deterioration and more by an AI capex escalation phase that pressures free-cash-flow optics, shareholder-return narratives, and valuation sensitivity.

Conversely, beneficiaries of that spending—AI infrastructure, semiconductors, and commodities—are supported by nearer-term revenue visibility and order momentum.

If USD weakness persists, relative support for non-U.S. markets may continue, particularly where the industrial cycle is favorable.

< Summary >

Big Tech and Nasdaq underperformance reflects an AI capex “arms race” that shifts cash from shareholder returns toward investment, increasing valuation headwinds.

AI-disruption narratives spread into financials through disintermediation concerns, with signs of aggressive pre-pricing and potential overreaction.

Declines in Palantir, Robinhood, and AppLovin are consistent with post-rally “leadership digestion” after 10x–20x advances over two years.

Capital is rotating from Big Tech as a factor into Big Tech capex beneficiaries: data centers, cooling, power, memory, and semiconductor equipment.

Potential USD weakness and the industrial cycle are supporting Korea/Taiwan (semiconductors), Japan (policy), and Brazil/Australia (commodities).

An additional driver may be a “private-market black hole,” as OpenAI/Anthropic IPO expectations absorb liquidity from listed growth equities into private and proxy exposures.

[Related Articles…]

- Asset Allocation Implications Under a Weaker U.S. Dollar Scenario

- Semiconductor Cycle: Why Memory, HBM, and Equipment Stocks Move Together

*Source: [ 소수몽키 ]

– 빠르게 돈 빠져나가는 빅테크와 나스닥, 새롭게 시장이 주목하는 주인공들

● Tokenization Tsunami, Korea STO Power-Grab, 24-7 Trading Shock

Why Asset Tokenization Will Reshape Finance in 2026: STOs, RWAs, Fractional Investing, and the Strategic Move Korea Is Missing

Key points covered in this report:

1) Why the market is structurally shifting from fractional investing to Security Token Offerings (STOs), changing the rules of the game

2) How Real-World Asset (RWA) tokenization is redesigning equity, real estate, and IP markets

3) Where “24/7 trading + fee restructuring + redistribution of distribution power” converge

4) In Korea’s STO agenda, why implementation delays matter more than legislative passage, and how winners are determined

5) A consolidated view of where capital and revenue pools ultimately flow (distribution vs. issuance)

1) One-line issue summary (news brief)

Tokenization converts rights to real-world assets into blockchain-based tokens (securities) that can be traded.

As Korea approaches regulated STO adoption from 2026 onward, market infrastructure (issuance, distribution, venues, and fees) is entering a restructuring cycle.

2) The rise of fractional investing: what drove rapid adoption

2-1. In practice, fractional investing is less about splitting ownership and more about splitting cash-flow rights

While marketed as “owning a piece of an asset,” many structures primarily fractionalize claims on income generated by an underlying asset.

Once positioned under capital markets frameworks, these products face recurring debates over whether they constitute securities.

2-2. How fractional investing expanded across asset classes

– Commercial real estate: platforms offering fractional exposure to rental income and appreciation

– Music royalties: platforms that tokenize or fractionalize royalty cash flows

– Art, luxury goods, collectibles: structures that provide exposure to price appreciation

– Livestock: structures that share profits and losses across breeding, feeding, and auction cycles

2-3. The primary market impact: large-scale production of “tradable rights”

Growth in fractional investing indicates that rights previously illiquid are increasingly packaged and distributed as standardized products.

The next step is converting these rights into tokens to enable more efficient secondary-market trading, reinforcing the shift toward STOs.

3) Tokenization and RWAs: not “micro-ownership,” but a distribution-structure overhaul

3-1. Defining RWA (Real-World Assets)

RWAs include real estate, art, IP rights, commodities, and receivables, where asset-linked rights are represented as digital tokens and managed and traded on-chain.

3-2. Security tokens: securities issued and recorded on blockchain infrastructure

Traditional dematerialized securities rely on centralized ledgers maintained by designated institutions.

Security tokens record ownership and transactions on distributed ledgers, changing the underlying infrastructure and affecting distribution costs, settlement speed, and auditability.

3-3. STOs: a term that simultaneously reshapes issuance and distribution

An STO refers to issuance of security tokens and the full lifecycle of their distribution and trading.

As the market scales, the strategic question shifts from “which assets are attractive” to “who controls issuance and who controls distribution.”

4) Blockchain essentials: why the “group chat” analogy captures the core

Blockchain links transaction records (blocks) into an immutable chain, stored and validated collectively by network participants.

Two core properties matter in financial-market applications:

1) Records are difficult to alter without network consensus

2) Updates propagate across participants rather than being controlled by a single centralized server

The financial implication is reduced “trust costs” across verification, settlement, audit, and intermediation, creating pressure to restructure transaction costs and fee pools.

5) Market implications: how venues and broker roles may change as security tokens scale

5-1. As security tokens scale, the competitive axis shifts from products to market design

Multiple global institutions have highlighted tokenization’s high growth trajectory, with an emphasis on expanding securitization-like trading into non-financial RWAs.

Key concurrent shifts include:

– Expansion of tradable hours toward near-24/7 market access

– Shorter settlement and post-trade cycles through reduced intermediation

– Fee restructuring driven by changes in who captures value across the trading stack

5-2. The U.S. signal: experiments with tokenizing listed equities

Public references by major U.S. exchanges to tokenization indicate strategic adoption beyond crypto markets and toward modernization of core market infrastructure.

In weaker macro environments, market participants often prioritize cost reduction and liquidity provision over leverage expansion, making tokenization a plausible tool for operational efficiency and liquidity design.

6) Korea STO: the key watch items extend beyond legislation

6-1. Legislative pathway toward STO authorization

Korea is advancing legal amendments to enable STOs within the regulated perimeter.

For investors, implementation details are more material than passage: subordinate regulations, supervisory guidance, and licensing frameworks will determine market structure and competitive outcomes.

6-2. Regulatory emphasis on separating issuance and distribution

A core policy direction is separation of issuers and trading/distribution operators to mitigate conflicts of interest and protect market integrity.

This functions as a structural constraint on vertical integration in tokenized securities markets.

6-3. Exchange operators vs. incumbent fractional platforms: the underlying conflict

The practical fault line centers on who controls secondary-market distribution.

– Many incumbent fractional platforms are positioning as issuers

– Some market participants aim to operate distribution venues

– Exchange and alternative trading operators are positioned to participate as market operators subject to licensing

Beyond licensing, distribution control determines:

1) Trading and behavioral data ownership

2) Fee capture across the value chain

3) Listing, review, and disclosure standards

4) Investor access and liquidity concentration

7) Core points often underemphasized in mainstream coverage

7-1. The decisive battleground is distribution rights and market design, not blockchain engineering

Distribution operators set practical standards (token specifications), fee schedules, listing rules, and access conditions, analogous to platform gatekeeping in digital marketplaces.

7-2. “Issuance-distribution separation” functions as a power-allocation mechanism

While framed as investor protection, the rule effectively determines how influence and economics are distributed between incumbent financial infrastructure and newer tokenization-native firms.

7-3. The primary cost of delay is the loss of network effects, not technology

Tokenized markets tend to concentrate liquidity in dominant venues, which then become de facto standards.

If domestic implementation lags, capital, issuers, and projects may anchor to overseas standards and distribution networks, increasing the risk that the domestic market becomes structurally secondary even after regulation is finalized.

7-4. The key trade-off is speed and experimentation design, not abstract fairness

Time-limited preferential frameworks have been discussed as a way to accelerate rollout while preserving incentives for innovators.

The central issue is designing a regime that enables rapid implementation without undermining participation incentives, otherwise market formation may occur offshore first.

8) Investor and professional checklist: what to monitor into 2026

Five indicators provide practical visibility into the transition:

1) STO subordinate rules and supervisory guidance: licensing requirements and liability allocation for issuers and venues

2) Scope of exchange and alternative venue participation: which tokenized asset categories will be permitted and where they may trade

3) RWA prioritization: early scaling potential is higher for assets with observable and contractible cash flows (e.g., rent, royalties, receivables)

4) Investor protection mechanisms: disclosure, suitability, dispute resolution, and custody frameworks

5) Fee and take-rate evolution: which intermediaries capture economics, and where costs compress or reappear across the stack

9) AI-trend linkage: where tokenized markets intersect with AI

AI can automate valuation, risk management, and price discovery; tokenized securities digitize issuance, distribution, and settlement.

Together, they enable more frequent updating of RWA valuations (e.g., rent trajectories, royalty projections, receivable default probabilities), which can flow into token prices and liquidity conditions with shorter latency.

This shifts the market from “fractional selling” toward more continuous repricing dynamics.

< Summary >

Tokenization is an infrastructure shift that converts rights to real-world assets into security tokens for trading and distribution.

Fractional investing accelerated the productization of previously illiquid rights; STO expansion shifts the competitive focus from technology to distribution-market design.

In Korea, the separation of issuance and distribution, and competition among exchanges, alternative venues, and tokenization-native firms, will materially influence implementation timing and market outcomes.

Delays increase the risk of losing network effects—liquidity concentration, standards, and fee-setting power—to offshore markets.

[Related Articles…]

- After STO institutionalization, three points that will reshape the security token market landscape

- RWA (real-world asset tokenization): a risk checklist to review before investing

*Source: [ 경제 읽어주는 남자(김광석TV) ]

– 토크나이제이션(Tokenization)이 가져올 금융시장 대변혁. 블록체인이 가져올 토큰경제 [경읽남 232화]

● Critical Minerals Crunch, Korea Manufacturing Survival Crisis

If Critical Minerals Are Not Secured, Korean Manufacturing Faces a “Survival” Risk, Not Just a Cost Issue (2026 Critical Minerals Supply Chain Conflict: Key Takeaways)

This report covers:1) Why the growth of the Fourth Industrial Revolution and AI increases the strategic importance of primary industries (mining).

2) Where Korea is most vulnerable in critical minerals bottlenecks (batteries, rare earths, refining).

3) How China built a “superpower” structure by controlling both upstream mining and midstream refining.

4) The underlying reasons behind the United States’ shift from multilateralism to bilateral agreements and the implications of a 180-day timeline.

5) Execution strategies Korea should change immediately.

1) One-line headline: “The first lever in the AI power race is minerals, not semiconductors”

As industrial complexity rises, the strategic value of mining increases materially. High-value sectors such as AI, semiconductors, and EV batteries rely on an interlocked chain—ore → refining → materials → components → finished goods—where disruption at any single stage can halt production. Current supply-chain restructuring is often framed as a technology conflict, but upstream critical minerals increasingly determine downstream outcomes.

2) Critical minerals are defined by impact, not volume

More than 50 metallic elements can be considered mineral resources; governments designate “critical minerals” based on a common logic:

- Essential to economic and national security

- Shortages create outsized damage

Korea designated 33 critical minerals in 2023; periodic updates are required as industrial demand shifts. The United States typically applies a broader scope, often around ~50.

3) “Large-basket” minerals vs “pinch-point” minerals in Korea

(1) Large industrial footprint (base metals)

- Iron, copper, zinc: large revenue and broad manufacturing use.

(2) Lower volume but high supply-chain risk (strategic minerals)

- Battery minerals (lithium, nickel, cobalt) and rare earths: small quantities can stop entire production lines. For Korea, this category represents higher systemic risk.

4) Why minerals concentrate in specific countries: geology, not politics

Resource concentration is primarily geological, driven by formation conditions such as tectonics, volcanism, magmatic fluids, and hydrogeology. The resulting distribution is structurally uneven and difficult to rebalance through market mechanisms alone.

5) Korea has minerals, but economically viable metal mining is constrained

Korea is relatively strong in industrial minerals (e.g., limestone), but has limited economically scalable metal-mining capacity. Even when deposits exist, conversion into operating mines is difficult due to:

- High development costs (labor and construction)

- Complex environmental regulation and permitting

- Low local acceptance (ESG can mitigate impact, not eliminate it)

As a result, Korea remains structurally dependent on imports for most critical minerals.

6) Korea’s primary procurement tools: equity stakes and offtake agreements

Two common mechanisms:

- Equity investment in overseas mining projects: secure volumes and/or profits proportional to ownership.

- Offtake agreements: lock in long-term supply volumes independent of equity position.

Mining investment is high-risk: exploration → development → infrastructure → operations require long lead times and face multiple uncertainties.

7) Substitution is feasible; “creating elements” is not

New elements cannot be produced via conventional chemistry. Practical approaches are:

- Substitution via materials and process innovation to reduce dependence on specific elements

- Metallurgical and refining innovation to improve extraction and separation from previously uneconomic feedstocks

8) Why China became a superpower: simultaneous control of upstream mining and midstream refining

Mineral deposits are globally distributed, but China secured influence by acquiring mine stakes and locking volumes through long-term contracts (including Belt and Road-linked channels). The decisive advantage is refining:

- Refining is energy-intensive, emissions-intensive, and requires deep infrastructure (power, water, chemical industrial base).

- Global players often avoided entry due to cost differentials, reinforcing China’s scale advantages.

- China’s midstream dominance, combined with upstream control, materially increased supply-chain leverage.

This structure matters because downstream vertical integration into semiconductors, EVs, and batteries is accelerating, contributing to fragmentation of global value chains.

9) U.S. response: technology controls vs China’s mineral export controls

The United States uses restrictions on equipment, chips, and software; China responds via controls on minerals (e.g., rare earths, gallium). This reciprocal bottleneck strategy increases systemic risk as trade volumes and mutual dependence shift.

10) Why 2026 becomes more consequential: U.S. shift from multilateral to bilateral critical-minerals agreements

The United States is reducing reliance on multilateral frameworks and increasingly locking critical-minerals supply chains through bilateral, state-to-state agreements. The “deliver results within 180 days” timeline signals an intent to secure concrete contracts and physical volumes, not policy statements. This approach can also function as leverage over allied partners.

11) Key point underweighted in mainstream coverage: Korea’s primary bottleneck is refining, not mining

Narratives often stop at “acquire mining stakes,” but refining and processing concentration—particularly in China—preserves supply-chain exposure even when upstream assets are secured. Mining access is a necessary but insufficient condition.

Recommended priority sequence for a Korea-specific strategy:

- Secure de-China refining and processing routes first (build midstream capacity within allied blocs).

- Structure offtake contracts to cover refined outputs and intermediates (not only raw ore).

- Focus domestically on high-value, permit-feasible segments: refining, recycling, and materials processing, rather than broad-based mine development.

12) Investor checklist for Korea (2026–)

Use the following as core diligence questions:

- Not only whether mineral prices rise, but where refining spreads (margins) and bottlenecks are forming.

- Not only which country imposes export controls, but whether alternative refining routes open with verifiable volumes.

- Not only whether a company bought a mining stake, but the offtake volume, duration, and product specification (ore, concentrate, intermediates such as nickel sulfate).

- Not only whether policy is announced, but whether permitting, power costs, wastewater handling, and carbon costs support a viable project model.

- Not only whether global value chains persist, but which bloc’s midstream role Korea can realistically anchor.

13) Embedded 2026 macro and industrial keywords

This theme links directly to inflation (input costs), interest rates (capex financing), exchange rates (imported unit costs), supply-chain constraints (bottlenecks), and recession risk (demand slowdown). Critical minerals are no longer a standalone resource-sector issue; they are an economy-wide variable shaping Korea’s manufacturing cost structure and national competitiveness.

- Competition in AI, semiconductors, and EV batteries increasingly begins with critical-minerals supply chains.

- Korea has limited metal-mineral self-sufficiency and must rely on overseas equity participation and offtake agreements.

- China built dominant leverage by combining upstream mining influence with midstream refining scale.

- The United States is restructuring supply via bilateral agreements and compressed execution timelines, alongside technology controls.

- Korea’s decisive battleground is securing de-China routes for refining, processing, materials, and recycling with contractually committed physical volumes.

[Related Articles…]

- https://NextGenInsight.net?s=critical%20minerals

- https://NextGenInsight.net?s=rare%20earths

*Source: [ Jun’s economy lab ]

– 광물 확보 못하면 한국은 위기가 옵니다(ft. 박준혁 작가 1부)